Ensemble l.46 cm Waneta meuble sous vasque d'angle blanc façade bois à poser + plan vasque d'angle céramique blanc | Castorama

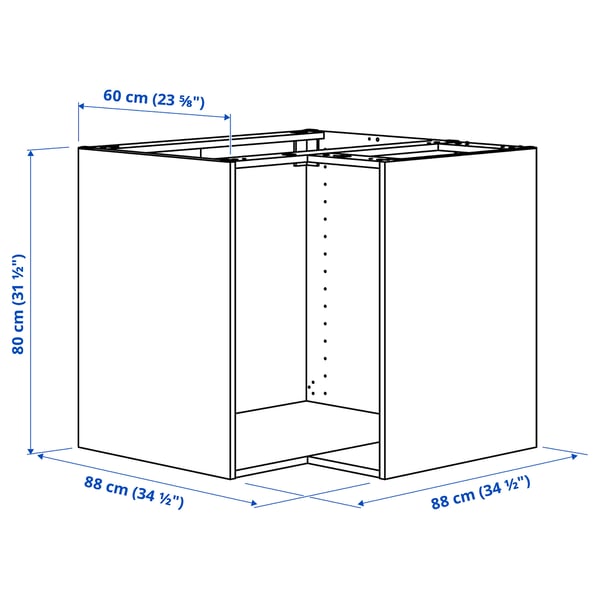

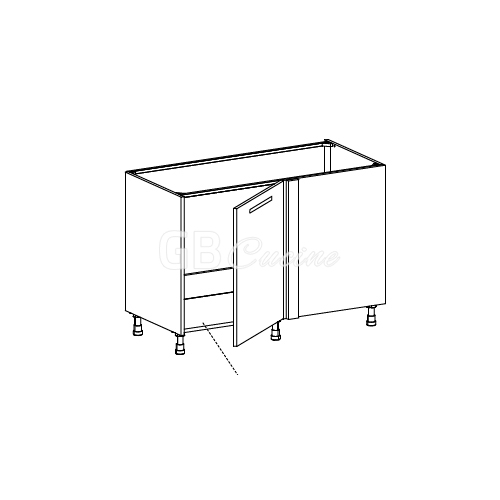

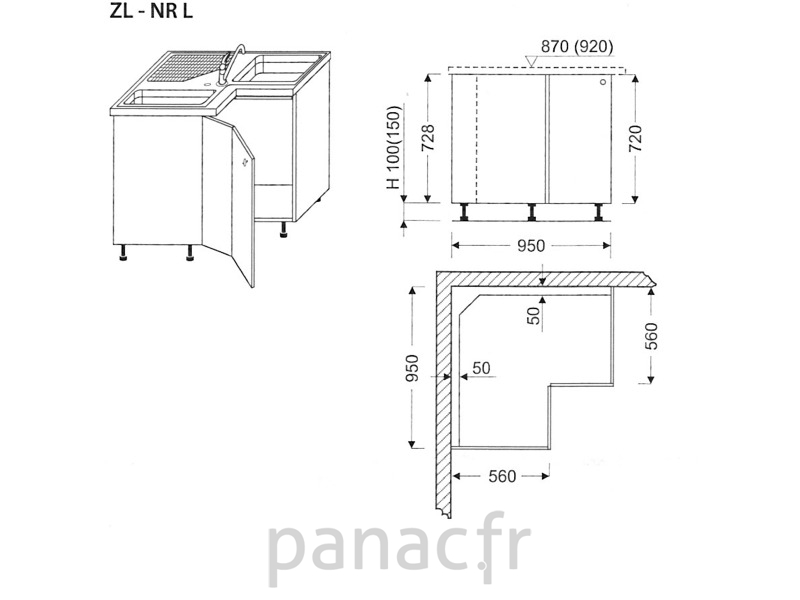

Meuble de cuisine Angle sous évier réversible IKORO Chêne clair 1 porte N°19 L40 cm L80 x H70 x P58 cm - Oskab

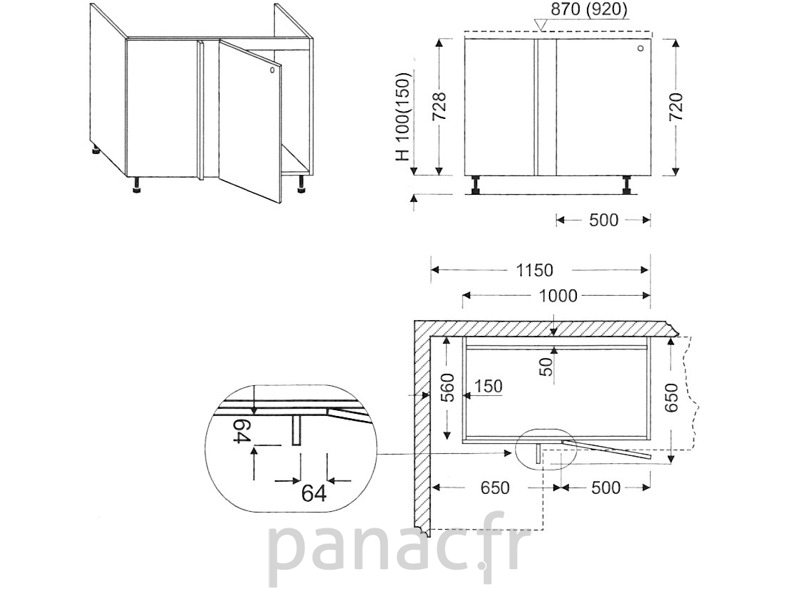

Évier de cuisine d'angle Blanco Metra 9 E - Sous-meuble 90x90cm - 830 x 830 x 190 mm - Noir - Vidage manuel - Blanco

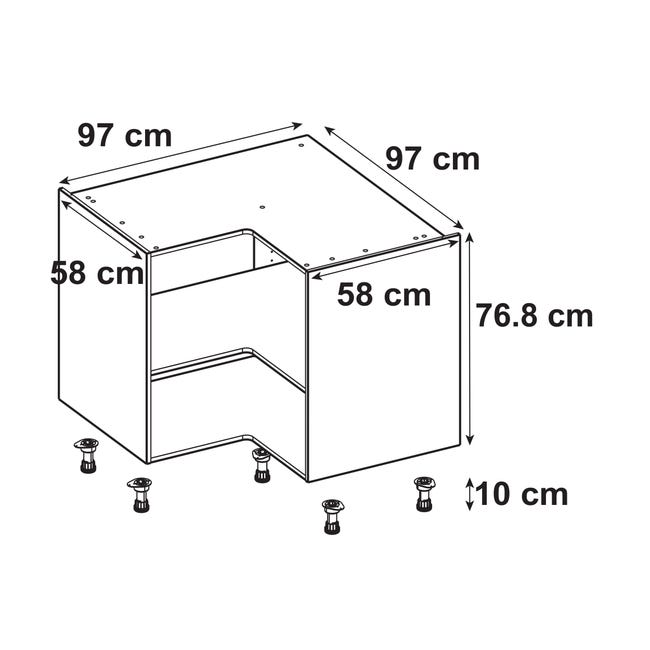

Meuble Salle De Bain, Meuble Sous Evier Salle De Bain, Petit Meuble De Salle De Bain D'angle Et Évier Utilitaire Lavabo Avec À Linge Évier Combiné Pour La Maison, La Cuisine, La